I have long had a craving for cranes…

…their haunting calls that seem to beckon back to prehistoric wildness,

bugling notes of a coming spring that echoes through time and place;

…their emergence from wetland reeds, wading into shallow waters,

or feeding in the stubble of recent crop harvest;

…their dancing - leaping, bowing, and flinging of sticks,

and the raring of colts, following their parents into the heat of summer.

…big birds with wide wingspans, long necks and bills, and red splashes atop their heads,

charismatic megafauna of wet prairies.

Cranes are impressive in their stature, appealing in their beauty, and noticeable in their unique sounds and displays. Whooping cranes are the tallest birds in North America, standing about five feet tall, with snow-white bodies and black wing tips that are rarely visible until they take flight. Sandhill cranes can reach four feet tall, with slate-gray bodies often tinted with some rusty red and various shades of browns and tans – influenced by constant preening and smearing of mud and soil on their feathers. Both whooping and sandhill crane adults have bright red markings on their heads that contrast with bright white head and body of the whoopers and the bright white cheek on sandhills.

Cranes dance and sing. A variety of bows, leaps, flaps, and throwing of sticks and other debris are forms of sign language, especially useful when courting and competing for mates in spring. Both crane species produce loud, resonating, bugling calls, that vary with what the birds are communicating. Sandhill cranes bugle a rattling call while whooping cranes have a clearer, higher pitched call. Cranes sometimes are confused with great blue herons, although they are quite different (see photos below). Herons do not dance. Their necks tuck into an “S” shape, and they are more commonly seen along river and lake shorelines. Cranes are birds of wetlands and surrounding grasslands, and, especially during migration, feed on waste grain in fields.

Extirpated from Iowa

The spectacle of cranes in Iowa is all the more treasured because nesting sandhill cranes were vanquished from the state for nearly a hundred years, and nesting whooping cranes are gone and unlikely to return. Both species nested in Iowa prairie-wetlands until the late 1800s, with sandhills being the most common. The last sandhill crane nest recorded in the nineteenth century was from a pair in Humboldt County (1884). It would be 98 years until a successful crane nest would be recorded in the state. During this period, rare glimpses or distant calls of migrating cranes was reserved for the luckiest of Iowans.

Cranes suffered from the near-total transformation of prairie-wetlands to Iowa farmland, taking away the required habitat for the birds to nest and feed their young. Unregulated hunting, mostly for food, but also for sport and pest control (cranes will feed on crop grains during fall migration), also impacted the population. And egg collectors frequented Iowa nesting grounds in search of prized 3.5 to 4-inch long sandhill or whooping crane eggs. Eggs from that last sandhill crane nest in 1884 were taken by a collector.

While nesting cranes were gone from Iowa, sandhill cranes still maintained a somewhat healthy population status in North America. This could not be said for whooping cranes, which in the 1940s had an estimated population of just 21 individuals and were considered to be on the brink of extinction. Efforts to restore the whooping crane population began in earnest in the 1970s with varying levels of success. A year-round population in Louisiana disappeared. The largest group of whoopers has grown to a fairly steady population of about 500 birds, nesting in and around Wood Buffalo National Park in Northwest Canada and wintering along the Texas Gulf Coast. A small eastern group of about 70 individuals also has been successful, nesting in Wisconsin and wintering in publicly protected lands in western Indiana and northern Alabama. Efforts to save the whooping crane is a story (or book) unto itself, with many ups and downs and dedicated conservation champions. Whooper sightings in Iowa are rare, with an occasional migrating bird spotted about once every couple of years.

In search of cranes

My first encounters with nesting sandhill cranes came while I was a naturalist with Buchanan County Conservation Board, on a ten-acre marsh surrounded by another 50 acres of wet meadow and hay ground habitat. It was the early 1990s, and John and Maxine Ham had donated the wetland portion of their farm to Iowa Natural Heritage Foundation upon their passing. This was about the same time that the first successful sandhill crane nests in modern times were confirmed in Otter Creek Marsh in Tama County (1992). Anecdotally, Ham family and friends had already been enjoying seeing and hearing cranes from March through October at their marsh, indicating nesting likely was occurring at this Buchanan County site. In 2007, the Buchanan County Conservation Board took ownership of the ten-acre marsh and also acquired the 50 acres of surrounding land to make Ham Marsh a public wildlife area (by then, I was the Conservation Board Director). With some wildlife management enhancements, Ham Marsh is now a public “birding hot spot” for observing sandhill cranes and a host of other wetland and grassland bird species.

During the early 1990s, interest in cranes was on the rise. Buchanan and Linn County Conservation Board partnered to provide motorcoach trips for Iowans to experience the spectacle of the great sandhill crane migration through Central Nebraska – one of the world’s most impressive mass wildlife migration events. The draw of cranes is such that people from eastern Iowa eagerly travel a thousand miles round-trip to witness more than a half-million cranes making their March spring migration stop along some sixty miles of Platte River corridor between Kearney and Grand Island, Nebraska. As sunset nears, wave after wave of the birds make their way to the “foot-deep, mile-wide” Platte River to wade or stand on sandbars overnight in the safety of the moving water. As the sun rises, the birds lift off in the thousands and fly to nearby fields and wetlands where they remain an attraction throughout the day, feeding and exhibiting courtship displays, as people drive the back roads with cameras and binoculars at their sides. On some trips, a whooping crane is seen among the big flocks of sandhills. The cranes in this western flyway are headed to the prairie marshes of the northern United States and Canada, some as far north as the arctic circle.

Back in Iowa

Iowa DNR waterfowl biologist Orrin Jones says that, “Although more monitoring is needed to fully know population trends, every indication is that sandhill cranes are increasing both in nesting success and abundance”. Wetland protection and restoration efforts, and carefully regulated hunting, have brought back a priceless gift to current and, hopefully, future generations of Iowans. There are still threats facing sandhill cranes, and it is important to protect, enhance, and expand important habit areas. One current threat is avian influenza, with an outbreak in Indiana recently causing sandhill crane deaths.

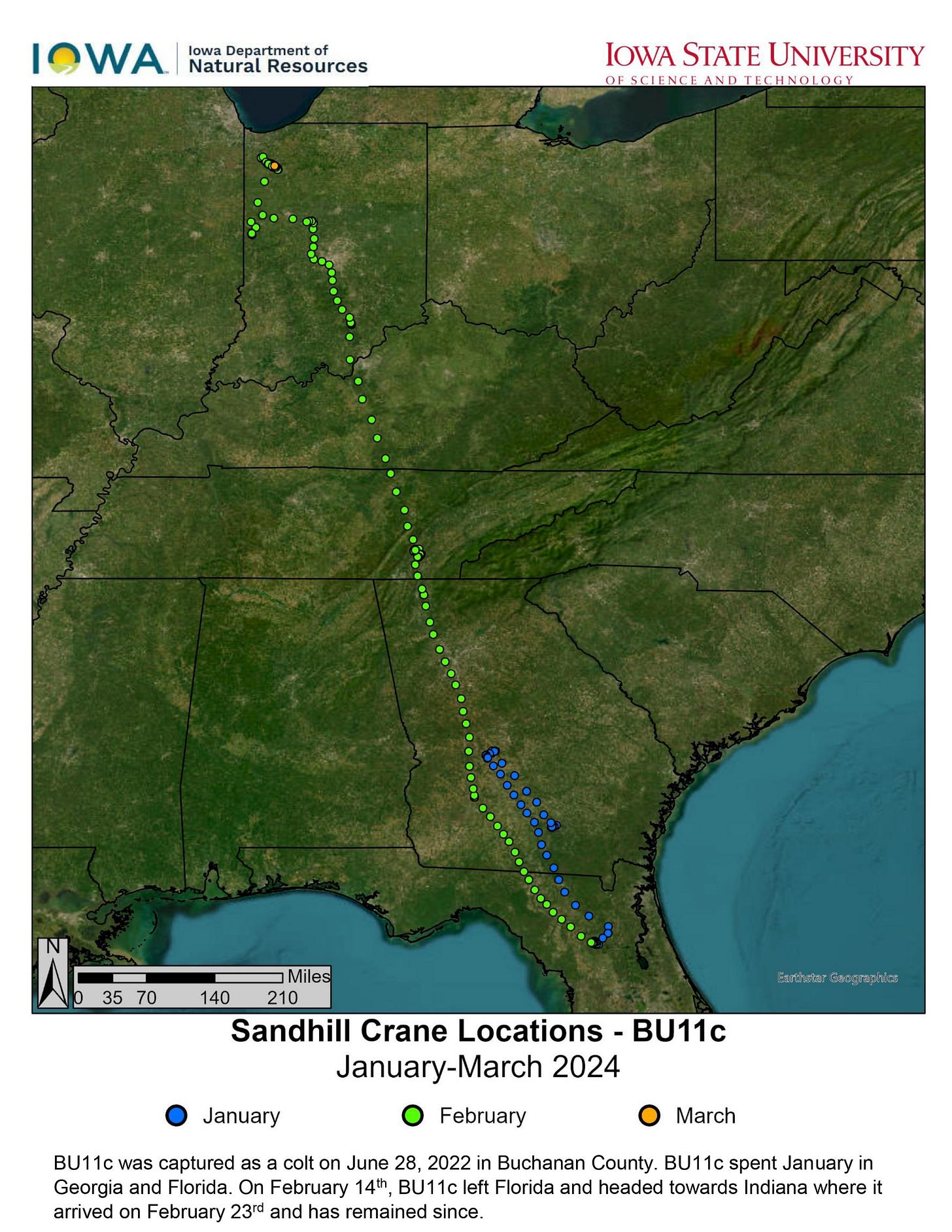

One ongoing sandhill crane research project is tracking birds born at Ham Marsh and other sites in Iowa. In 2020, through a partnership between Iowa DNR and Iowa State University, biologists placed transmitter tags on the leg tarsals of five sandhill crane colts. According to Jones, the pilot project had several objectives, including determining how best to capture and tag the birds, whether the transmitters would last into adulthood (3-5 years), and what types of information could be gleamed from the data. Funds also were obtained to tag more birds in 2022 and 2023, resulting in a total of forty tagged young cranes. The objectives seemingly are being met, and researches are learning a lot about the movements of individual cranes, the distances they travel, and the places they frequent – nesting, wintering, and migrating. They now know that Iowa sandhill cranes are tightly associated with the eastern population that winters in the Southeast United States.

Sandhill crane BU11c was captured and tagged in a field adjacent to Ham Marsh in 2022. The bird spent the summer with its parents in and around the Marsh, headed off to the Mississippi River in October, hung out there for about a month, and then made its way southeast, eventually wintering in Georgia and Florida. In its first spring back in Iowa, it took off on a long excursion, checking out numerous prairie-wetlands in Iowa, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, in one week traveling more than 600 miles before settling back in Iowa. Jones says this is typical of young cranes in their first couple springs. “For the first three months back they seem to be prospecting various wetland habitats, likely honing their selection for a precise future nesting site”, said Jones. In 2024, BU11c began his trip back, and made it as far as southern Indiana before the transmission was lost. Jones says, “we can’t say with certainty what has happened with BU11c, but knowing the avian influenza outbreak was occurring at that same time leads us to fear this bird may have died.”

Tagged birds from 2022 now are entering their third spring, when some will attempt to nest and raise colts for the first time. The trasmitters are still working as hoped, and Jones says they are looking forward to analyzing data from this year’s movements. Hopefully, there will be some good first-time nest success. Sandhill cranes typically have good nest fealty - returning to the same approximate locations where they previously had success raising colts.

In search of whoopers

Iowa is once again home to sandhill cranes, but to see and hear whooping cranes is rare or requires a bit of travel. From late March to November, whooping cranes can be found in central Wisconsin. Last October, my wife Micki and I made a trip to see the impressive, white birds in Necedah National Wildlife Refuge, about 75 miles northeast of LaCrosse, Wisconsin, and we were not disappointed. These cranes are part of the introduced eastern population that the International Crane Foundation (located near nearby Baraboo, Wisconsin) estimates to consist of 68 individuals as of 2024. They find places to nest in the Nacedah’s 43,696 acres consisting almost entirely of managed wetlands.

Whoopers also can be seen in their wintering grounds along the Texas Gulf Coast, most notably in and near Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, east of Corpus Christi. This is the major wild population from which the eastern introduced population was derived. In December, after watching the Iowa State Cyclones football team lose the Big 12 Championship Game to Arizona State in Dallas, I made my way to the Gulf in search of cranes and other wildlife. The whooping cranes were there, stalking the wetlands and flying overhead at sunset on their way to evening roosts, like they have done for millennia. The ages-old call of cranes continues.

Wonderful article! I can often hear them waking up along the Iowa River not far from my house! Their comeback is a great success story.

Wow. Just read it again. Sandhill cranes provide hope that things can get better. Also noticed you took some very nice pictures... :)